English

10th-century missionaries to Norway concerned themselves with establishing chapels, churches and other ecclesiastical centers. Thus far, archaeological exploration has revealed traces of wooden churches with embedded posts. Some of these early wooden churches disappeared due to neglect as well as fire and other natural disasters, but the rest were replaced by new construction. Nevertheless, 28 of the stave churches built after the year 1100 still survive. This website presents information and research materials illuminating the medieval stave church from several perspectives: the architectural, from the carpenter’s point of view; the ecclesiastical, from the fervent Christian bishop’s point of view; and the secular, from the socially oriented patron’s point of view.

This page documents the work by Jorgen H. Jensenius (1946-2017), archictect, Ph.D. specialized in surveying and researching medieval wooden churches. His credentials include a life-long employment with the Central Office of Historic Monuments and Sites, and the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research in Oslo. The page is currently maintained by his son Alexander Refsum Jensenius.

Post, stave and stone churches

Travelling Norwegians must from early times have seen both wooden and stone churches of different sizes and constructions abroad. Craftsmen, who accompanied long expeditions to maintain the boats and to erect storage buildings and houses at their destinations, may have worked in local construction teams and learnt foreign practices. Features of foreign building practice may therefore have been current around Norway long before the attempt to convert the country to Christianity. During the Christianisation period in Norway, wooden churches and chapels were built, and traces have been found of over 30 of what are presumed to have been churches or chapels with a corner post structure. From the end of the 11th century, stone churches were also built, and more than 150 stone churches out of perhaps three hundred in total have been preserved. But in Norway more churches were built of wood than of stone, and out of perhaps over a thousand originally, 28 stave churches have been preserved.

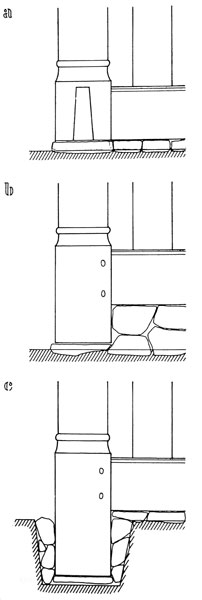

It is not known how many alternative designs the builders had to choose between when building the early Norwegian wooden churches, but the type that has so far been uncovered by archaeological excavation consists of buildings with posts dug into the earth. Posts are the vertical, roof-bearing timbers that were placed in excavated post holes. Staves are the vertical, load-bearing timers in the building. The frame of a stave church wall consists of a sill, staves and a top sill; these have grooves that receive the wall planks.

The churches have been investigated and described for more than 160 years. Some authors claimed that the churches had been built by foreigners, whilst others said that the churches were re-used ancient Norwegian places of worship. When excavations were made at the Urnes stave church in 1956, post holes belonging to older churches were found. The majority of descriptions of the churches of the Christianisation period before approx. 1960 are therefore out of date.

Today we consider the churches to be important expressions of their time that also describe the Church as an institution, identify bishops and describe the landscape, reveal the finances of the client, and tell us about wooden buildings in Norway in general. Tree ring examinations tell us about the age of the buildings. Studies from abroad provide comparative information about master builders, architects and craftsmen, economy, design and planning, the connection between texts and monuments, and about wooden structures, as well as about missionary work, canon law and liturgy.

In general there was a churchyard around the parish churches, of a suitable size for the requirements of the congregation. New churches may often have been located at the same place as the older church buildings, as this minimised the disturbance to earlier graves. If the churchyard was also new, it was ideally supposed to be blessed at the same time as the consecration of the church. The bishop’s consecration of the building and blessing of the surrounding area must have been seen as creating a sanctuary, in principle confirmed and guaranteed by the king.

By interpreting traces that can tell us about how the builders of the stave churches organised their work, how they selected and prepared materials, systematised elements, and erected, altered and rebuilt the churches, the history of a building can be described. There are still many questions that can be asked in relation to the wooden churches, as each generation sees them differently.

The origin of the wooden churches in Norway

The wooden churches of Norway are described and discussed in different ways for the last 160 years. Where did they come from? Were they reminiscent of pre-Christian temples? Were they copies of churches in England, Denmark, or Germany? Were they inspired from Byzantium or even The Far East?

The early missionaries who worked to spread the Gospel in Northern Europe encountered a wide range of building styles, but common to them all was the use of wood, and the first churches in most of the newly converted territories were therefore built of this material. The missionaries brought with them the features, practices and traditions of their own background. They may also have tried to introduce architectural elements of an imaginary or real tradition, like descriptions of the Temple in Jerusalem or St. Peters’ in Rome. To what extent this was a formulated program of design is not known. There must have been many wooden churches in Northern Europe in the early Middle Ages but these buildings have left very few traces. As a result not much is known about them, not even how long they lasted. In any event the Church had no normative policy in church building; the control of new churches was obviously left to the decision of the local bishops. Wood or stone, with or without aisles, large or small, opulent or simple, these were matters for the individual community to decide. It is to be assumed that the churches were built mainly as copies of older buildings. Symbolic explanations were added or deducted from the finished buildings for reasons of exegesis. When copying the next time, the building could be slightly changed due to the new symbolism. There was a migration of the iconic image of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem; pictorial representations showing this and other buildings are well known in the Middle Ages. Such pictures include both real and imaginary concepts of Jerusalem and of well-known churches. They are descriptions with varying degrees of accuracy, but at their best, they may provide valuable information about structural systems. Among medieval models are the ones held by the donors, patrons or saints. The form and construction of these models may be very general.

The transferring of ideas of architecture may have been a minor part of the Christian mission to Norway, but it may have been a strong wish to enhance the idea of universality of the Church through the architectural tradition as well. Acceptance of Christianity by the Norwegians was not simply a matter of confessional change, of dogma, or of religious belief and observance. The diffusion of a Roman ethnocentricity brought Mediterranean customs, values, and habits of thought to Northern Europe. The means for this was literature, books and the Latin language in addition to Roman notions about liturgy, law, authority, property and government, even if it was brought via England or Germany. As far as we know, the Church generally wanted churches to be built anew. There were probably no norms for size, material or form of church buildings ever given by the ecclesial authorities. A wooden church was undoubtedly expected to have certain properties, characteristics or qualities different from vernacular buildings. Churches consist of elements adjusted to function and use, defined in a European ecclesial tradition. The Christian mystery is derived from the Eucharist, and not from the volume created around the place of worship. The function of a church is its use, and the main use of a church is the liturgical practice. This practice requires room for movement and action. The Divine Service was not centred on a cult object and did not need a special altar.

It seems that the responsibility of bishops and people in the local church was emphasized: to build in the vernacular tradition, with inspiration of prototypes from elsewhere. The ecclesial prescriptions seem to admonish that a designer work from principles, not just from paradigmatic forms. Following the same line of thought, the essence of this early, wooden architecture must be the detailed, technical knowledge of the way the building was planned, designed and put together. All buildings are the result of a planning and design process, however modest the construction may seem, and however unrecognized such a process was by the people it involved. In the ecclesial tradition the normative seems to have consisted in the copying of churches from abroad, certain prototypes were seen as norms. But even without written codes or norms, unspoken traditions may have been influential in planning and design of churches. The number of variations seems endless, no two churches seem to be replicas of one another.

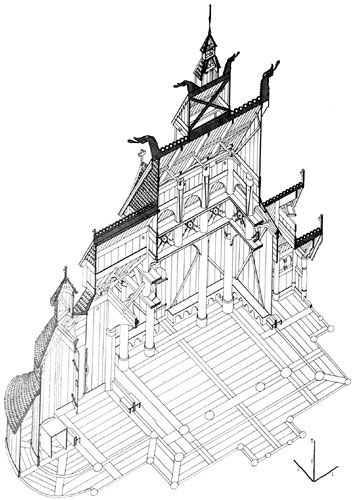

The preserved Norwegian wooden churches from the 12th century and onwards are one-aisled or three-aisled. In the three-aisled buildings the four rafter beams in the nave form a rectangle by being half-lapped into each other so their surfaces are flush and form the floor level with floorboards in between. The sill beams were beams placed edgewise. The sill beams are mortised approximately midway into the corner posts, fastened with wooden pegs. Along the upper edges of the sills were grooves for the tongues at the lower ends of the wall planks. The top end of the planks connects to the wall plate. The wall plate consists of two beams placed on their narrowest faces, one above the other. The posts, in the centre room, borne by the rafter beams, are roughly centred in the rectangle formed by the joints of the beams. The arcading between the posts carrying the centre room consists of quadrant brackets and an arc segment. Above the centre room is an open roof structure in which each truss consists of one set of rafters, one set of scissor braces and one collar beam. The trusses are supported by arcading. The plank roof lay on purlins which were let into the rafters so that the upper faces of the rafters and purlins were on the same level. The roofs are often covered by wooden shingles.

Transfer of the knowledge of building form from one country to another must have happened with the travelling of craftsmen. This travelling may have been of two kinds: Norwegian craftsmen visiting building sites in other countries, or craftsmen hired from abroad. In the first case, the Norwegian craftsmen would experience, learn and remember; they would bring new ideas back home. In the second case one could also expect vernacular practices from another country to be transferred to Norwegian soil. In addition, the sort of order the craftsmen had received is important. On the one hand, he could have been told to copy a prototype; on the other hand, the specifications could have been rather general, just with the main characteristics of a church.

Norse traders, raiders and mercenaries must have become acquainted with Christianity in the 8-9th centuries, if not earlier. Nordic chieftains who settled temporarily in the Viking territories of Western Europe may have allowed themselves and their followers to be baptized as a part of their stay to follow the habits of the locals. The first wooden churches in Denmark were erected in the towns of Slesvig and Ribe, following the establishment of the archiepiscopal see of Hamburg in 831. So, even before the arrival of the first missionaries in Scandinavia, Norse craftsmen travelling abroad may have become acquainted with how to plan, design and construct churches. Many of these early churches were of wood and the principal load-bearing elements consisted of earth-bound posts. In the early 12th century, the most common way of building wooden churches in Norway was with the posts/staves on low foundations of stone. The early wooden churches of Norway may have been built by the kings, the nobility, gentry and others encouraged by the kings and the missionaries. Broadly speaking, three parties were involved in planning, design and construction, namely the bishop, the patron and the craftsmen. The bishop represented the tradition of the international Church; the patron was responsible for ensuring that sufficient funds were available, while the craftsman with his knowledge discussed the possible solutions with the two others. They would then have an overall expression of church form, but it would be recognizably Norwegian in its materials, construction, joining and treatment of details.

Craftsmen apprenticed into a building tradition in Norway could combine another building tradition with their own vernacular when returning from foreign lands. To design a new church they had to combine the memory of a church somewhere else to their vernacular way of building; they glued new knowledge of form into existing knowledge. The carpenter had to find a scheme, or schemes, that had a given floor area and height, as a combination of economy, requirement, topography, climate, construction, materials, traditions, prototypes and aesthetics. This had no particular answer; each craftsman would give an answer bearing his own distinctive signature of the local tradition. The tradition represented the sum of the knowledge acquired by generations of builders before him. He was therefore duty-bound to follow the old methods and to copy the old forms, and tradition ensured that practices of proven worth were handed down to succeeding generations of craftsmen. They all had to work different techniques out by trial-and-error, to adjust the necessary, the economic, the practical and the beautiful to easily remembered and easily executed rules of thumbs. If the builder wanted a church similar to another, the rules of ratios would also have to be similar to the prototype. Even one length taken from another church may have been accepted as a “copy”.

One may presume there were both general and detailed norms regulating the design and construction of medieval wooden churches; concrete, contextualized descriptions communicating fundamental aspects of praxis. Since there are no historical “oral mnemonics” available for study we have to interpret from the building remains. For the builders knowledge of form was the means; while utility and economy were the ends. In most cases, there were not many options for what form the design of a church should take, the plan and elevation was in its basis a pragmatic labour of craft. Churches were copied selectively by imitating sequences of actions and were adapted to vernacular materials and economies. Design and construction were developed by individual trial and error. Builders were empirically trained and apprenticed by physically copying, by use of an undercurrent oral and tangible communication in team-working, leadership, analysis and problem-solving. In this interrelationship between thought and action the individual builder did the remembering, but all memories were attached to members of the social group of builders. Systematic thinking on knowledge of form was transferred through the ages as a “living” narrative text, with intervention, development and change by different builders at different times.

So, as far as we know, the wooden churches of Norway from medieval times are a complicated mixture of different European and Middle Eastern traditions, together with the older local building practices of Norway.

Literature

The problem of the genesis of the Norwegian wooden churches has been debated for more than 160 years. The painter I. C. Dahl (1788-1857) saw the churches as relicts of an advanced medieval wood building tradition which was rapidly disappearing. He asked the architect Franz W. Schiertz (1815-1887) to survey the Borgund, Heddal and Urnes churches for his book on the stave buildings, to support a general interest in preserving them for the future. This initiative contributed to the establishing of Fortidsminneforeningen in the year 1844. From that time on, the most important documentation and research on the churches has been published in their annual journal.

In the first thorough investigation of the Norwegian medieval wooden churches, Lorentz Dietrichson in his 1892 book recognised the unique status of the buildings. His idea was that the buildings for the most part were a graceful transformation of forms from European stone churches into wood. Many researchers have tried to connect visual form to similar forms in churches elsewhere, by tracing wooden forms back to a supposed stone origin. The question is whether the churches were inspired by foreign ecclesiastical buildings, whether they were copied from vernacular Norwegian houses, or something in between. Riksantikvaren, the Central Office of Historic Monuments and Sites, was established in 1912. Many of the researchers specializing in wooden church architecture were employed here. In general, the descriptions of the buildings and the understanding of the development of the history of architecture have been following that of Dietrichson. After 1950, however, building archaeology, excavations outside and inside buildings, extended documentation and dendrochronology have given new knowledge on topography, planning, design, technology, construction, decoration, artifacts and inventory. As in churches elsewhere, the Norwegian wooden churches are the result of a complicated vernacular and international tradition. So far, no complete description has been made of any of the churches. The books mentioned here will give the reader important fragments of the history of the medieval wooden churches.

Medieval Wooden Churches in Northern Europe, Especially in Norway

- 2011: Krogh, Knud J.: Urnesstilens kirke. Pax. Oslo.

- 2009 Christie, Håkon: Urnes stavkirke: den nåværende kirken på Urnes. Oslo, Pax, i samarbeid med Riksantikvaren. ISBN:978-82-530-3245-0, ib.

- 2005 Anker, Leif og Jiri Havran: The Norwegian Stave Churches. ARFO. Oslo. ISBN 82-91399-29-8

- 2004 Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn: The Awakening of Christianity in Iceland. Discoveries of a Timber Church and Graveyard atÞórarinsstaðir in Seyðisfjörður. PhD Thesis. GOTARC, Gothenburg Archaeological Thesis, Series B No 31. Göteborg.

- 2003 Egenberg, Inger Marie: Tarring maintenance of Norwegian medieval stave churches. Characterisation of pine tar during kiln-production, experimental coating procedures and weathering. Doctoral dissertation. Göteborg Studies in Conservation 12, Göteborg.

- 2002 Storsletten, O.: Takene taler, Norske takstoler 1100-1350, klassifisering og opprinnelse. Con-Text, avhandling 10, Arkitekthøgskolen i Oslo.

- 2001 Ahrens, C.: Die frühen Holzkirchen Europas, B. I-II, Stuttgart.

- 2001 Jensenius, J.H.: Trekirkene før stavkirkene. En undersøkelseav planlegging og design av kirker før ca. år 1100. Con-Text,avhandling 6. Arkitekthøgskolen i Oslo.

- 2001 Solhaug, M. B.: Middelalderens døpefonter i Norge, vol. I-II,Acta humaniora; no. 89, (dr. philos.) Det historisk-filosofiske fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo.

- 2000 Anker, L.: Stokk eller stein?: Kirke, byggemåter og mulige byggherrer i indre Sogn om lag 1130-1350 belyst ved et utvalg kirker fra perioden. Hovedfagsoppgave i kunsthistorie. Universitetet iOslo.

- 2000 Fernie, E.: The Architecture of the Norman England. Oxford.

- 1999 Hohler, E. B.: Norwegian Stave Church Sculpture. Vol. I-II, Oslo.

- 1999 Schjelderup, H. og O. Storsletten (red.): Grindbygde hus i Vest-Norge: NIKU-seminar om grindbygde hus. NIKU Temahefte 30. Oslo.

- 1989-1999 Berg, A.: Norske tømmerhus frå mellomalderen, vol. I-VI,Oslo.

- 1998 Zimmermann, W.H.: Pfosten, Ständer und Schwelle und der Übergang vom Pfosten- zum Ständerbau – Eine Studie zu Innovation und Beharrung im Hausbau, Probleme der Küstenforschung im südlichenNordseegebiet, vol. 25: 9-241.

- 1997 Anker, P.: Stavkirkene, deres egenart og historie, Oslo.

- 1996 Blair, J. and C. Pyrah (reds.): Church Archaeology, Researchfor the Future. CBA Research Report, no. 104. London.

- 1995 Christensen, A.L.: Den norske byggeskikken, hus og bolig pålandsbygda fra middelalderen til vår egen tid. Oslo.

- 1994 Skov, H.: Hustyper i vikingetid og tidlig middelalder, Hikuin:139-162.

- 1994 Weinmann, C.: Der Hausbau in Skandinavien vom Neolithikum biszum Mittelalter. Berlin, New York.

- 1993 Berg, A. (med fl. red.): Kirkearkeologi og kirkekunst: Studiertilegnet Sigrid og Håkon Christie. Øvre Ervik.

- 1990 Qvale, Wencke: Lorentz Dietrichsons verk om “De norske stavkirker” og dets plass i norsk stavkirkeforskning. En analyse av en forskningstradisjon. Avhandling for magistergraden i kunsthistorie, Universitetet i Bergen. Mangfoldiggjort.

- 1983 Murray, H.: Viking and Early Medieval Buildings in Dublin, BAR, British Series, vol. 19. London.

- 1983 Ólafsson, G. (red.): Hus, gård og bebyggelse. Reykjavik.

- 1982 Ahrens, C.: Frühe Holzkirchen im nördlichen Europa. Hamburgisches Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Hamburg-Altona.

- 1982 Drury, P.J. (ed.): Structural Reconstruction. Approach to the Interpretation of the Excavated Remains of Buildings. BAR British Series, vol. 110. London.

- 1982 Fernie, E.: The Architecture of the Anglo-Saxons. London.

- 1982 Myhre, B. (m. fl. red.): Synspunkter på huskonstruksjoner i Sør-Vestnorske gårdshus fra jernalder og middelalder, AmS-skrifter,vol.7. Stavanger.

- 1981 Christie, H.: Stavkirkene – Arkitektur, Norges kunsthistorie, b. I-VII, Oslo: I, 139-252.

- 1981-1996 Christie, S. og H.: Norges kirker, Buskerud, b. I-III.Oslo.

- 1976 Hauglid, R.: Norske stavkirker. Bygningshistorisk bakgrunn og utvikling. Oslo.

- 1974 Christie, H.: Middelalderen bygger i tre, Oslo.

- 1973 Hauglid, R.: Norske stavkirker. Dekor og utstyr. Oslo.

- 1970 Anker, P.: The Stave Churches, in: The Art of Scandinavia,vol. I-II, London etc.: I, 200-452.

- 1966 Olsen, O.: Hørg, hov og kirke, Aarbøger for nordisk oldkyndighed og historie, 1965.

- 1956-1978 Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder, København.

- 1914-16 Ekhoff, E.: Svenska stavkyrkor: Jämte iakttagelser över de norske samt redogörelse för i Danmark och England kända lämningar avstavkonstruktioner. Stockholm.

- 1892 Dietrichson, L.: De norske stavkirker, Kristiania.

- 1891 Bruun, Johan: Norges stavkyrkor. Ett bidrag till dän romanska arkitekturens historia. Akademisk avhandling (Filosofisk doktorgrad). Stockholm.

- 1845- Foreningen til norske fortidsminnesmerkers bevaring, årboken.Oslo.

- 1837 Dahl, I.C.: Denkmale einer sehr ausgebildeten Holzbaukunst aus den frühesten Jahrhunderten in den innern Landschaften Norwegens. Dresden.